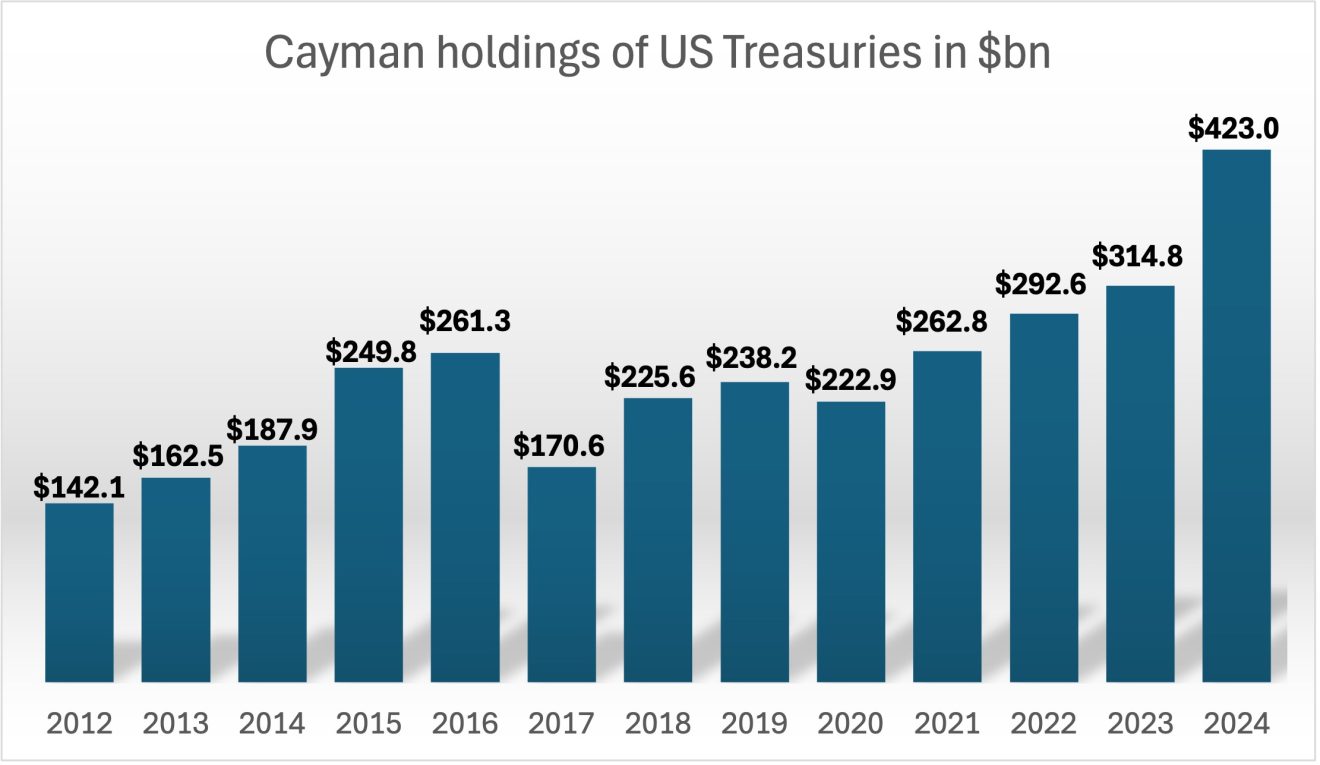

Every few months, data from the US Treasury Department sparks a round of news articles that may appear curious. The Cayman Islands, a small Caribbean territory with a population of just 90,000, consistently ranks among the world’s largest foreign holders of US government debt – often rivalling China, Japan, or the UK.

For policymakers and the public, the optics can be confusing. How could such a small offshore centre possibly bankroll Washington’s ever-growing borrowing needs? The answer is simple. The billions of dollars’ worth of Treasuries attributed to the Cayman Islands are hedge fund positions.

Cayman is the legal home for much of the world’s hedge fund industry, which pools capital from global investors. Cayman-domiciled hedge funds raise money from pension funds in Canada, sovereign wealth funds in the Middle East, or wealthy families in Asia. Even though these funds are typically managed from New York or London, when those vehicles buy US Treasuries, the official statistics chalk it up to the Cayman Islands, from where they are administered.

Why hedge funds hold Treasuries

To understand why hedge funds hold a significant portion of Treasuries, it is necessary to examine how modern bond markets operate. Unlike pension funds or central banks, hedge funds do not buy Treasuries for yield or safety. Instead, hedge funds use Treasuries as the raw material for a variety of leveraged, or debt-funded, trades.

These so-called “relative value” trades aim to capitalise on small price misalignments between Treasury bonds and certain derivative contracts linked to them in highly liquid markets.

One of the most popular is the cash–futures basis trade. A hedge fund buys a Treasury bond, usually funding the purchase through short-term borrowing in the “repo” market, while simultaneously selling a futures contract on the same bond.

A Treasury bond futures contract is a standardised agreement to buy or sell U.S. Treasury bonds at a future date for a price agreed upon today. The investor only needs to maintain a margin deposit and does not have to pay the full notional amount upfront. This means the Treasury futures investor can initially speculate on, or hedge against, interest rate movements affecting the value of the bond for a fraction of the cost of buying the Treasury security immediately.

As a result, Treasury bond futures trade at a slight premium to the actual Treasury bond. Over time, the prices will converge because the Treasury bond must be delivered at the end of the futures contract.

The hedge fund pockets the price difference. On paper, this is low risk. In practice, because the spreads are minuscule, funds employ enormous leverage to make the trade worthwhile. They use the purchased US government bonds as collateral, or security, for short-term loans in the repo money market, thereby amplifying the returns by up to 100 times the capital they put down.

According to 2024 estimates, basis trades alone now account for about $1 trillion in positions, supported by some $2.5 trillion in hedge fund repo borrowing.

Another popular play is the “swap spread trade,” which involves going long in Treasuries while shorting interest rate swaps — a way to profit if the yield difference between the two narrows.

How the market evolved

The rise of hedge funds in the Treasury market is a result of two long-standing shifts.

First, banks, once the dominant “primary dealers” tasked with absorbing Treasury issuance, have been reined in by post-2008 regulations. Basel III rules forced them to hold more capital against all assets, even very safe government bonds, and imposed leverage ratios that made it costly to warehouse large inventories.

Then, central banks, which had been the largest buyers of government debt under quantitative easing for years, began to retreat. As banks and central banks scaled back, hedge funds, with their appetite for leverage and fewer regulatory constraints, filled the gap. In the US, they now account for approximately 11% of the Treasury market – an extraordinary share for market participants once considered peripheral. Hedge funds that report to the SEC held a gross value of nearly $3.4 trillion in US Treasuries at the end of 2024.

The alleged risks behind the numbers

Hedge funds have helped keep Treasury markets liquid at a time of massive government borrowing and constrained bank balance sheets. Yet critics say their dominance brings new risks. Unlike primary dealers, hedge funds have no obligation to make markets in times of stress. Their behaviour is opportunistic. In calm markets, they supply liquidity as a byproduct of their arbitrage activities. But when volatility spikes, they can exit en masse.

Some critics point to the events of April 2025 as a prime example. A sudden tariff announcement jolted rate markets. Margin requirements on futures surged, repo costs jumped, and both basis and swap spread trades turned sour. Funds began to unwind positions simultaneously, exacerbating selling pressure in Treasuries and widening bid-ask spreads. Rather than stabilising the market, it is claimed, hedge funds acted as accelerants of volatility. Yet it is not clear how much basis trades really contributed to the market movements.

There is also a concentration problem. In the UK gilt market, regulators have found that fewer than ten hedge funds account for the vast majority of leveraged positions. Similar patterns exist in the US. When so much market-making rests on so few players, it is argued, the risk of disorderly unwinds grows.

This can happen, for example, when prices in a basis trade diverge rather than converge. Loan counterparties will demand more collateral, forcing hedge funds to either raise additional capital or unwind the trade. Failing that, the trades will unravel as lenders seize the underlying collateral.

Even some hedge fund managers acknowledge that basis trades could, in theory, contribute to the instability of the Treasury market; however, they argue that the market is already inherently unstable, primarily due to the ample supply of government debt.

Looking ahead

The dynamic is unlikely to end soon. As long as there is a steady supply of US government debt, futures and swaps markets to arbitrage, and repo financing is available, funds will continue to trade.

What may change is the regulatory response. An SEC attempt to force hedge funds to register as broker-dealers was rejected by a Texas federal court last year.

Still, some in Washington and Basel argue for higher margin requirements and central clearing of US Treasury secondary market transactions.

Some industry associations counter that such measures could make markets more unstable if they prompt sudden deleveraging.