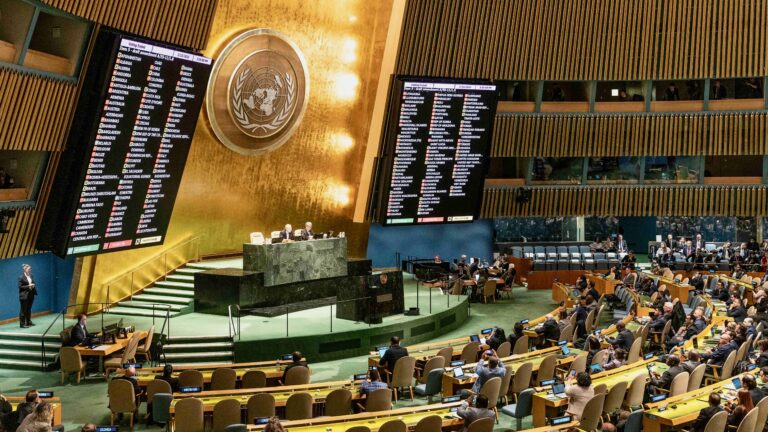

Just as the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) was about to launch a global minimum corporation tax and new international corporate tax rules, the United Nations General Assembly, in November 2023, approved a resolution that will enable the organisation to start work on a legally binding UN tax convention.

Supporters of the resolution celebrated the vote as historic and a win for developing countries and the Global South. Opponents in mostly advanced economies argued it would lead to a duplication of efforts made by the OECD in the reform of international taxation that could undo much of the progress that has been made.

While it is not immediately obvious how the UN would be more adept at creating a new international tax framework, it appears inevitable that negotiations will shift to the global intergovernmental organisation.

Developing countries and civil society pressure groups have long sought to wrest control of international tax policymaking away from the OECD. They have criticised the Paris-based standard setter as not inclusive enough and favouring the world’s larger and wealthier economies that form its membership.

In 2022, a group of African countries successfully brought a UN resolution that called on the UN secretary-general to produce a report that would present different options to strengthen the “inclusiveness and effectiveness” of cross-border tax cooperation and give the UN a more prominent role in international tax matters.

More inclusive and effective

The report published by the UN secretary-general, António Guterres, in August 2023 noted certain shortcomings of the existing international tax architecture, such as barriers to engagement for developing countries in the OECD’s decision making processes.

The OECD, in response to the criticism, said it had a proven track record enabling significant changes in the international tax landscape that had benefited developed and developing countries.

This included progress in international tax transparency and information exchange; efforts to curb tax base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS); the reform of purely residence-based tax rules in a more digitalised and globalised economy (Pillar One), and a global minimum corporation tax rate of 15% (Pillar Two).

In the tax sphere, the OECD is indeed acting on behalf, and at the instruction, of the G20 and its 39 OECD members. Many developing countries are part of the OECD/G20’s Inclusive Framework, which includes 145 member countries and territories that work on the implementation of the BEPS project, as well as the development of Pillar One and Two.

But for economic and procedural reasons many lower-income countries believe, and the UN report found, that the Inclusive Forum does not provide them with satisfactory participation and effective influence on agenda setting and decision making.

They argue that globalisation and digitalisation have only widened the gap between developed and developing economies and created a form of tax injustice that allows large multinational companies to participate in a country’s digital economy without paying much, or any, tax.

Of the tax reform proposals, specifically Pillar One is not considered to be in the best interest of developing countries, due to its limited scope and the fact that expected additional tax revenues are mostly going to be collected by advanced economies.

Pillar Two may have a more positive effect on developing nations but is seen as equally difficult to implement and overly complex. In addition, the global minimum corporation tax rate of 15% is for many countries too low to end tax competition between them.

Groups of African, Latin American and Asian countries therefore hope that international rules for tax cooperation under the UN will be more representative of developing countries than the OECD.

The UN report concluded that the UN’s role in shaping tax norms and setting tax rules can be enhanced to make international tax cooperation “fully inclusive and more effective”.

The report said there was already a consensus on the need to “strengthen international tax cooperation to combat tax avoidance and evasion and illicit financial flows, which drain much needed resources especially from developing countries; and build more fair, inclusive, and effective tax systems, which are essential to building the trust and spurring the transformation envisaged in the global sustainable development agenda”.

Framework convention on tax

Against the will of mostly OECD members and other developed countries, which pushed for a non-legally binding solution, the resolution passed in November 2023 approved the development of a UN framework convention on international tax cooperation.

Framework conventions are legally binding treaties subject to the general rules of international treaty law. They can function as a foundation of universally accepted commitments, with additional, more ambitious protocols layered on top that countries can opt into on a case-by-case basis.

What this framework convention will cover is not yet clear. The resolution calls for the creation of a UN member state-led, open-ended ad hoc intergovernmental committee to draft the terms of reference by August 2024. The terms of reference will then be subject to negotiations.

The committee is further tasked with preparing a progress report for the UN General Assembly to consider at its 79th session in September 2024.

However, the resolution has not set a deadline for the finalisation of the convention itself.

Previous reports by the UN hint at some of the proposals that could be included in the terms of reference.

In 2021, a high-level UN panel called for a complete overhaul of the global tax system, which included a UN tax convention, a UN tax body and a global minimum tax included in the tax convention.

The UN High Level Panel on International Financial Accountability, Transparency and Integrity (FACTI) report outlined several policy priorities for a UN tax convention, such as effective capital gains taxation, public country-by-country reporting, and a mechanism to address international tax disputes.

In terms of digital taxes, the report said a UN tax convention could “create a multilateral framework based on international agreement and enable additional countries to start taxing the digital economy with realistic prospects of obtaining substantial revenue.”

The report also called for a global pact for financial integrity for sustainable development. This agreement would use proceeds from tackling illicit financial flows to fund UN sustainable development projects.

Another idea raised by FACTI involves a new centre that would collect the data necessary to fight global tax avoidance and evasion. This information could include declared corporate profits, real economic activity of multinationals, the location of assets and their beneficial owners, and international tax cooperation mechanisms.

Ambitious and vague

Given the multiple objectives of the various parties involved, the UN framework convention will be a massive project.

To achieve the floated ideas of inclusiveness, fairness and effectiveness, together with linkups to development and sustainability goals, while reducing complexity, supporting the global trade in goods and services, and fostering cross-border investments is both incredibly ambitious and vague.

The focus on what the UN calls ‘illicit financial flows’ as a source of potential tax revenues, often based on unscientific estimates by civil society groups, borders on the improbable.

All this comes against the backdrop of the UN having so far neither the funding nor any expertise in international tax matters. It took the OECD decades to develop the technical capacity and a decade more to build consensus on its initiatives.

Proponents have argued that there should be no duplication of efforts between the UN and the OECD, not least because many developing countries lack the capacity to second experienced tax staff to one, let alone two international organisations.

FACTI, in its report, suggested the OECD could be used as part of the UN process. The OECD Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes, the UN high-level panel said, could become a related organisation to the UN, like the International Organization for Migration.

Professional staff from the OECD and the UN could work together at a new UN tax secretariat.

Why OECD members should be supportive of such a proposal, having voted almost universally against the UN resolution is not clear.

The notion that the UN could offer an alternative to the consensus-based approach of the OECD, which would somehow favour developing nations in international tax matters, for instance through a form of majority voting, is unrealistic.

The vote on the tax framework convention has reflected the same bi-polar geopolitical fault lines that have hampered decision-making in international affairs generally at the UN. The existing uneven power dynamics between developed countries and their multinationals and the developing world also remain in effect.

The OECD, meanwhile, has said it will continue its work on the implementation of Pillars One and Two.

The negotiations of the UN framework convention will therefore lead to more, rather than less, complexity in international tax matters.