While the sovereign right of countries to set advantageous tax rates to attract investments is widely recognised, the OECD has argued that tax competition had resulted in a race to the bottom of corporate tax rates with deleterious effects for government revenues worldwide.

The creation of a global minimum tax at an effective corporate income tax rate of 15% would therefore create a level playing field and limit tax competition by putting a floor under it.

Yet, none of these statements is correct. While statutory headline corporate tax rates have fallen on average, from 28.1% in 2000 to 20% in 2022, the total intake from corporate taxes has, in fact, increased.

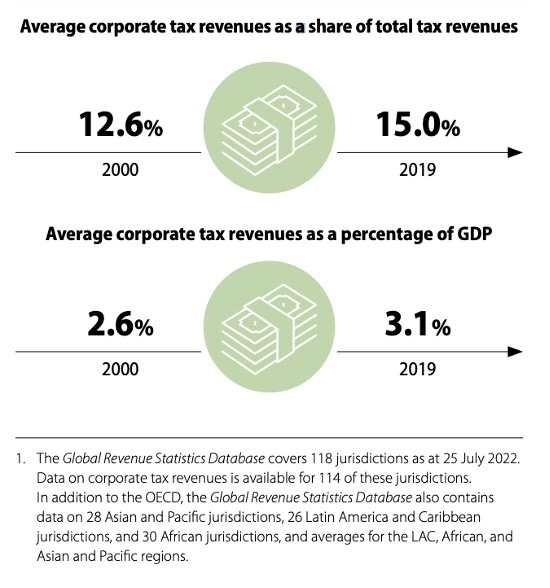

The OECD’s own Corporate Tax Statistics, published last year, showed that in the 20 years up until 2019 corporate tax revenues in 114 analysed countries grew both as a share of total tax revenues from 12.6% to 15%, and as a percentage of GDP, from 2.6% to 3.1%.

During that time, total tax revenues as a percentage of GDP in OECD countries have increased as well, from 32.93% in 2000 to 34.11% in 2022.

In other words, despite lower nominal rates, corporation taxes have increased their share of a growing pie.

As far as tax competition is concerned, there are several reasons why the global minimum tax may not be very limiting, either.

Tax rate competition is not going away

Firstly, a minimum tax of 15% will not prevent competition among countries with tax rates above 15%.

Secondly, companies that fall outside the reach of the global minimum tax – because they have annual turnover of less than EUR750 million – can still be subject to lower tax rates than 15%.

Even countries with no or low corporate tax rates that announced they would implement the global minimum tax locally have no plans to apply the tax to companies below the Pillar Two revenue threshold.

This is in part the result of the introduction of the qualified domestic minimum to-up tax (QMDTT). The QMDTT was a late addition to the new rules. It gave zero- and low-tax countries first dibs at taxing corporate income at source themselves at a minimum rate of 15%.

Some high-tax countries are now viewing the development with concern as it changed the character of the rules and reduced the amount of tax they will be able to collect.

Some believed the global minimum tax would have forced low-tax countries to raise their taxes to the minimum rate even without a QMDTT. But then such a tax would have had to be applied to all companies, not just those with a turnover of EUR750 million or more.

As it stands, a joint study by the Centre for European Policy Studies and the European Capital Markets Institute noted that the introduction of a QMDTT could in fact increase the incentives for certain jurisdictions to offer low- or zero rates to corporate entities.

The author Apostolos Thomadakis wrote that the QMDTT allows a country to collect revenue that would otherwise be collected elsewhere, while maintaining competitive taxation for companies that are not covered by Pillar Two through either low tax rates or extensive tax relief.

Tax competition is shifting towards substance

For large multinationals that fall under the Pillar Two rules, in turn, tax competition would not disappear but simply take other forms.

In the OECD’s thinking, tax competition based on tax rates alone does not reflect real economic activity and is considered harmful. However, countries are still allowed to compete for what the OECD deems to be real and productive investments.

The Pillar Two rules therefore contain substance-based carve-outs that reduce the tax-base to which the minimum tax rate is applied. The deductions begin at 8% for tangible assets and 10% for payroll, before they are gradually reduced to 5% each over a 10-year period.

It is only plausible that such substance-based carve-outs could lead to a new form of substance-based tax competition.

Business professors Reinald Koch and Dominika Langenmayr wrote in an op-ed for German newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung: “If production takes place in low-tax countries, the resulting profit, up to the amount of the substance-based allowances, does not fall under the minimum tax. Whereas companies previously shifted only profits to low-tax countries, they now have an incentive to shift production.”

They argue that the global minimum tax re-incentivises competition for real economic activity rather than just profits but conclude for Germany that implementation costs will be high and tax revenue effects benign at an estimated 0.2% of total tax revenues.

Fellow German business professor Christoph Spengel and his team, in their analysis for trade magazine Der Betrieb, go even further by demonstrating that it can be advantageous for German companies to shift economic activity, such as shared service centres, abroad to reduce taxes due under Pillar Two.

This is because some European countries offer tax benefits for income from patents and trademarks or treat expenses for research more favourably.

The academics illustrate, using Belgium and Ireland as examples, that it can be advantageous for a German corporation to outsource business functions like accounting, IT, human resources, call centres, or factoring to separate entities abroad to avoid additional tax.

By shifting real economic activities, low-tax regimes can still be taken advantage of, while top-up taxes are minimised, they write.

Their conclusion: What was intended to curb profit shifting could potentially result in something more undesirable – the relocation of real economic activities abroad.

Shift away from corporation tax benefits to other tax incentives

As the minimum tax applies only to corporation taxes, tax competition could also shift away from corporation tax to energy taxes, property taxes, indirect taxes, payroll contributions and other non-tax factors, according to Thomadakis.

Sweden, for instance, offers a 97% tax cut on any electricity used by data centres, which reduces electricity bills by 40%.

In addition, tax competition could exploit certain features of Pillar Two. Corporate tax incentives that do not reduce the tax base of company, but which are paid as tax credits, in other words reimbursements of taxes and levies that are due, are still allowed under the rules.

In a nod to the United States and its vast green subsidies contained in the Inflation Reduction Act, the latest OECD guidelines issued in July 2023 also include marketable transferable tax credits, which can be sold to third parties, as a form of income rather than a reduction of covered taxes.

Covered taxes are used as the numerator in the calculation of a company’s effective tax rate under Pillar Two, whereas income is the denominator.

Jurisdictions that want to maintain their fiscal competitiveness and still comply with Pillar Two could simply change certain tax rebates such as R&D, patent box and fast depreciation into marketable tax credits or qualified tax credits that are refundable against other taxes, Thomadakis wrote.

By doing so the effective tax rate will be higher, while the benefit to the company remains the same.

Any reduction in tax competition in terms of lower rates could thus simply be substituted by intensified tax competition through tax credits.