Michael Klein

The US has always publicly supported the global minimum corporation tax, developed by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) as part of a wider reform of international tax rules.

However, its actual position is more nuanced.

The initial motivation of the US administration was not to uncover new tax revenues with the help of the OECD but to thwart the imposition of unilateral digital taxes on mostly US multinational tech companies in their largest overseas consumer markets.

The negotiation process, which is still ongoing, delayed any changes to the status quo.

International discussions also gave the US government more time to influence what the new rules should look like, rather than face immediate tax losses and calls by American lawmakers for retaliatory measures.

In October of 2021, more than 130 member jurisdictions, including the US, reached an agreement on the framework for new international tax rules, built upon two primary pillars.

Under Pillar One, the world’s largest corporations would pay more taxes in countries where they have a large customer base, and fewer taxes in jurisdictions where they are headquartered or have operational activities.

The aim is to tackle the effect of the digital economy, which allows many businesses to grow significant commercial activities in markets without having to pay any corporation taxes there.

In addition, the international accord introduced a mechanism to set a global minimum corporate tax rate of 15%, which would increase taxes for companies generating earnings in low-tax jurisdictions (Pillar Two).

Although this Pillar Two was mainly pushed for by France and Germany, it may well have been a sweetener to convince the United States to accept the reform of residency-based taxation.

On the face of it, the US stands to lose from Pillar One and to gain more than other countries from a global minimum tax.

It is the country with the highest number of multinational corporations and the largest amount of overseas profits in low-tax jurisdictions.

According to the Congressional Research Service about 69% of the foreign profits of U.S. multinationals are in countries that have low or no corporation taxes.

However, on closer inspection the new rules could cause the US lost tax revenue and limit the ability of Congress to set tax policy.

US has its own version of a global minimum tax

Crucially, the US does not need Pillar Two. It already has its own version of a global minimum tax that applies to its multinational companies – the tax on global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI).

There is also the base erosion and anti-abuse tax (BEAT), a 10% minimum tax that applies to certain corporate payments, such as interest and royalties, to related foreign entities and is designed to prevent profit shifting out of the United States.

Rather than adopt what has been developed by the OECD, the US government tried to adapt its existing taxes to conform to the new rules.

The Build Back Better Act would have increased the GILTI tax rate and imposed it on a country-by-country basis, together with other amendments, to align GILTI rules with Pillar Two.

The US administration’s fiscal year 2023 budget proposals would have repealed BEAT and replaced it with elements of Pillar Two, including a domestic top-up tax and an undertaxed profits rule (more on this below).

But the changes were not adopted by US lawmakers.

Instead, the Inflation Reduction Act adopted an alternative minimum tax on large corporations, which is largely incompatible with the global minimum tax.

Doing nothing could cost the US tax revenue

Not adopting Pillar Two is problematic for the US and could lose the country corporation tax revenue.

Because countries are sovereign in passing their own tax laws and some may not be inclined to increase their tax rates to a universal minimum, the OECD devised a complex set of rules in its attempt to achieve an effective corporation tax rate of 15% globally.

The model rules released in December 2021 apply to multinational companies with a revenue of more than €750 million in two of the last four years, the same threshold that applies to country-by-country reporting requirements.

Pillar Two would impose a rate of at least 15% on the earnings of large multinationals in each of their operating countries via a top-up tax.

It requires companies to calculate an effective tax rate (ETR) for all constituent group entities in each country. If the ETR is below 15% anywhere, taxes would be applied to bring the tax rate to that level.

There are substance carve-outs, but they are applied to income after the ETR has been determined. The deductions would begin at 8% for tangible assets and 10% for payroll, before they are gradually reduced to 5% each over a 10-year period.

Pillar Two consists of three main rules to raise effective tax rates to a global minimum.

- First, the country in which an entity operates can impose its own top-up tax, known as a qualified domestic minimum top-up tax (QDMTT), to bring an entity’s ETR up to 15%. For example Bermuda and Switzerland are now looking at implementing such a tax, which would also apply to subsidiaries of multinational companies.

- If the source country does not impose a top-up tax, the country in which the ultimate parent entity is located can impose a top-up tax on the parent entity under the income inclusion rule (IIR). This will incorporate the income of the foreign constituent entity, which has an ETR of less than 15%, in the income of the parent company in such a way that its tax rate is raised to the minimum threshold.

- If the parent entity’s home country does not adopt the income inclusion rule, then all other countries in which the multinational corporation has constituent entities could increase the effective tax rate on those affiliates operating within their borders by applying the undertaxed profits rule (UTPR). The UTPR would in practice allow countries to deny any tax deductions and thus create additional tax liabilities to an extent that would equal the amount theoretically required to raise the low-tax jurisdiction’s entity’s ETR to 15%.

There is also a fourth rule, the subject to tax rule (STTR), which can be applied in a tax treaty framework to tax payments that would otherwise be subject to only a minimal tax rate. The rate for this rule is set at 9%.

What happens when the US does not adopt the global minimum tax?

The way the rules are designed, a US multinational’s operations could be affected both domestically and abroad.

The undertaxed profits rule would allow foreign governments to raise additional tax on a US corporation’s subsidiary in their home countries if the parent entities’ ETR in the US is below 15%. For example, if a US corporation only pays 10% effective tax in the US, France could require the company’s subsidiary in France to pay more tax.

Likewise, if the US does not adopt the income inclusion rule (IRR), foreign subsidiaries of US corporations could be taxed by third countries under the UTPR, if the company has constituent entities in low-tax jurisdictions that pay less than 15% corporation tax.

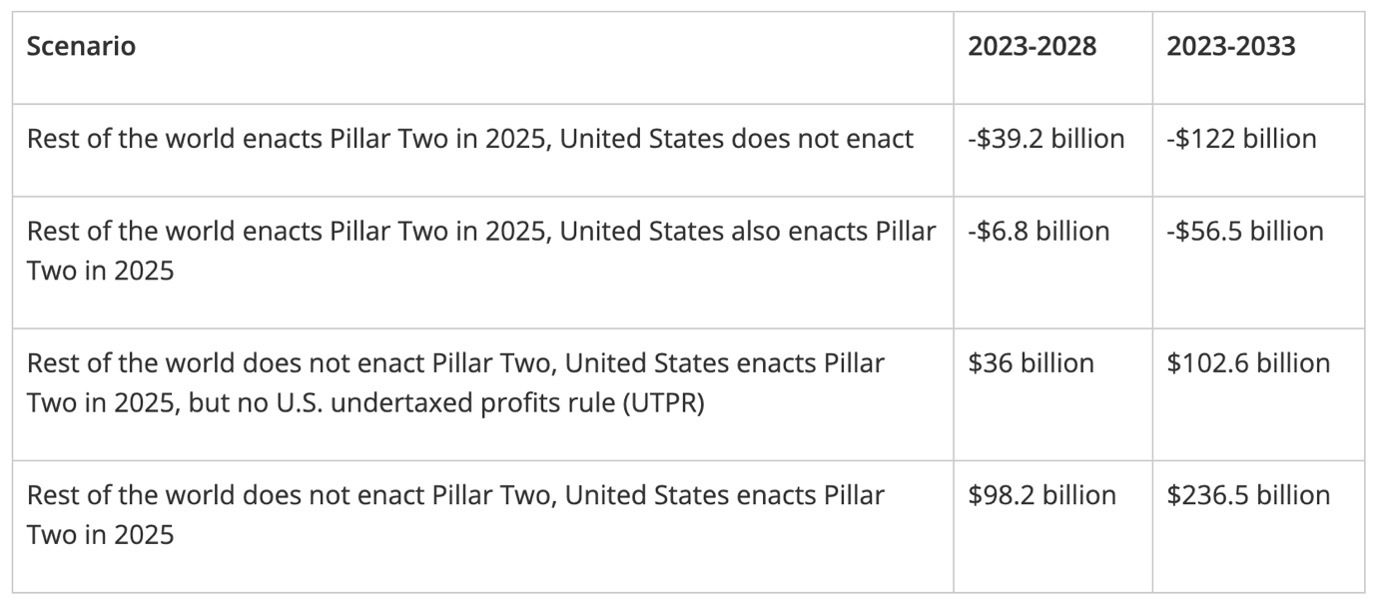

The nonpartisan Joint Committee on Taxation of the US Congress has estimated that if the rest of the world adopts the new rules while the US does not, the US could lose $122 billion in tax revenue over a ten-year period.

If both the rest of the world and the US adopt Pillar Two in 2025, the US would still lose $56 billion between 2023 and 2033, according to the analysis.

In contrast, if the US were the only country to adopt the new rules, it could gain $236.5 billion over the same period.

The rules are so complex that estimates if the US will lose or gain tax revenue from the global minimum tax vary wildly.

An August 2023 study by the Tax Foundation, admitting considerable uncertainty, calculated that foreign Pillar Two adoption would result in larger tax credits for US corporations that reduce US tax receipts by $64.3 billion over 10 years. In addition, the think tank predicted more reported income in the US would raise revenues by $99.3 billion for a net gain of $34.9 billion over a decade.

However, the agreement would also result in significantly lower post-corporate-tax incomes for U.S. shareholders, which would reduce U.S. individual income tax collections from taxes on dividends, capital gains, and retirement plan distributions.

“Given the high uncertainty surrounding policy and corporate behaviours, we are unable to definitively state whether foreign adoption of Pillar Two will raise or reduce U.S. tax revenues,” the study concluded.

Legislative changes required

Predictions are also made more difficult because it is unclear how many countries adopt the new rules and if the US changes its own tax laws. It is likely that a significant part of the world will implement the global minimum, as early movers seek to be rewarded with higher tax revenue.

The European Union has already adopted the global minimum tax and member countries are now implementing the rules in domestic law. In addition, there are several important US trading partners, such as Switzerland, that have announced they would adopt Pillar Two and impose their own QDMTT.

The US, in turn, will be hard-pressed to change its tax laws in line with the global minimum tax.

Congressional Republicans are adamantly against Pillar One and they have been irked by the undertaxed profits rule of Pillar Two.

They believe the deal would raise taxes on US companies mostly for the benefit of foreign governments and view the minimum tax as a threat to domestic investment and the ability to offer tax incentives, like tax credits.

Some have threatened retaliation should countries apply the UTPR to US companies.

“If other countries move forward to attack U.S. jobs and tax revenues through the UTPR, Congress will be forced to pursue additional remedial measures to protect American interests,” said Rep. Jason Smith (R., Mo.) and Sen. Mike Crapo (R., Idaho) in a joint statement.

OECD offers delay

To avoid this potential conflict and give US lawmakers more time to bring domestic tax legislation in line with Pillar Two, guidance by the OECD in July delayed the application of the UTPR until 2026 in countries where the headline tax rate is at least 20%.

The U.S. corporate tax rate is 21%.

Whether the delay is enough to push through legislative change is questionable.

Republican lawmakers favoured a solution that would grandfather the way GILTI is applied as compliant with the minimum tax.

GILTI uses a blending structure across subsidiaries allowing companies to offset taxes paid in high-tax countries against and taxes paid in low-tax countries. This is at odds with Pillar Two which applies a minimum 15% rate in each jurisdiction and would allow entities of US companies to have a lower ETR than 15%.

But in February 2023, the OECD clarified that GILTI will be considered a qualifying, controlled foreign company (CFC) tax regime under the Pillar Two rules. The guidance allows US tax on GILTI income to be allocated to low-tax jurisdictions, which would in effect result in less top-up tax imposed.

However, these blended CFC allocation rules are complex and set to expire in 2027.

The Tax Foundation, in its revenue study, argued that even if the US changed its international tax provisions to become more compliant with Pillar Two it would not automatically increase revenues. This is because, even though the country-by-country approach of the global minimum tax would raise more revenue than the U.S. blended system, Pillar Two’s substance carveouts are more generous to taxpayers early on.

Tax credits or subsidies

The OECD guidance also clarified the treatment of tax credits. US tax credits, such as those included in the Inflation Reduction Act which deploys hundreds of billions of dollars in incentives to encourage the adoption of clean energy technology to combat climate change, are treated as tax reductions under OECD rules.

The application of tax credits in the US could potentially cause a company to fall below the 15% ETR threshold and thus owe more taxes elsewhere in the world, undermining the desired effect.

The tax credits are tradeable in a fledgling market where companies looking for a tax break can pay between 80 and 95 cents on the dollar to clean energy firms without tax liability.

The OECD update set out that for tradeable tax credits only the net benefit – the difference between tax credit and purchase price – will be treated as a tax cut.

In general, the Pillar Two rules distinguish between qualified refundable tax credits and non-refundable tax credits. Both reduce a company’s tax liability, but a refundable tax credit pays out and is treated as income if no tax liability exists. Non-refundable tax credits are treated as a reduction in covered taxes.

The effect of Pillar 2 thus influences tax policy by favouring outright subsidies over tax incentives.

Whatever the effect will be in terms of tax revenue and policy, it is clear that the complexity of the rules will result in an extensive reporting burden and higher compliance costs for multinationals.